Olive growing

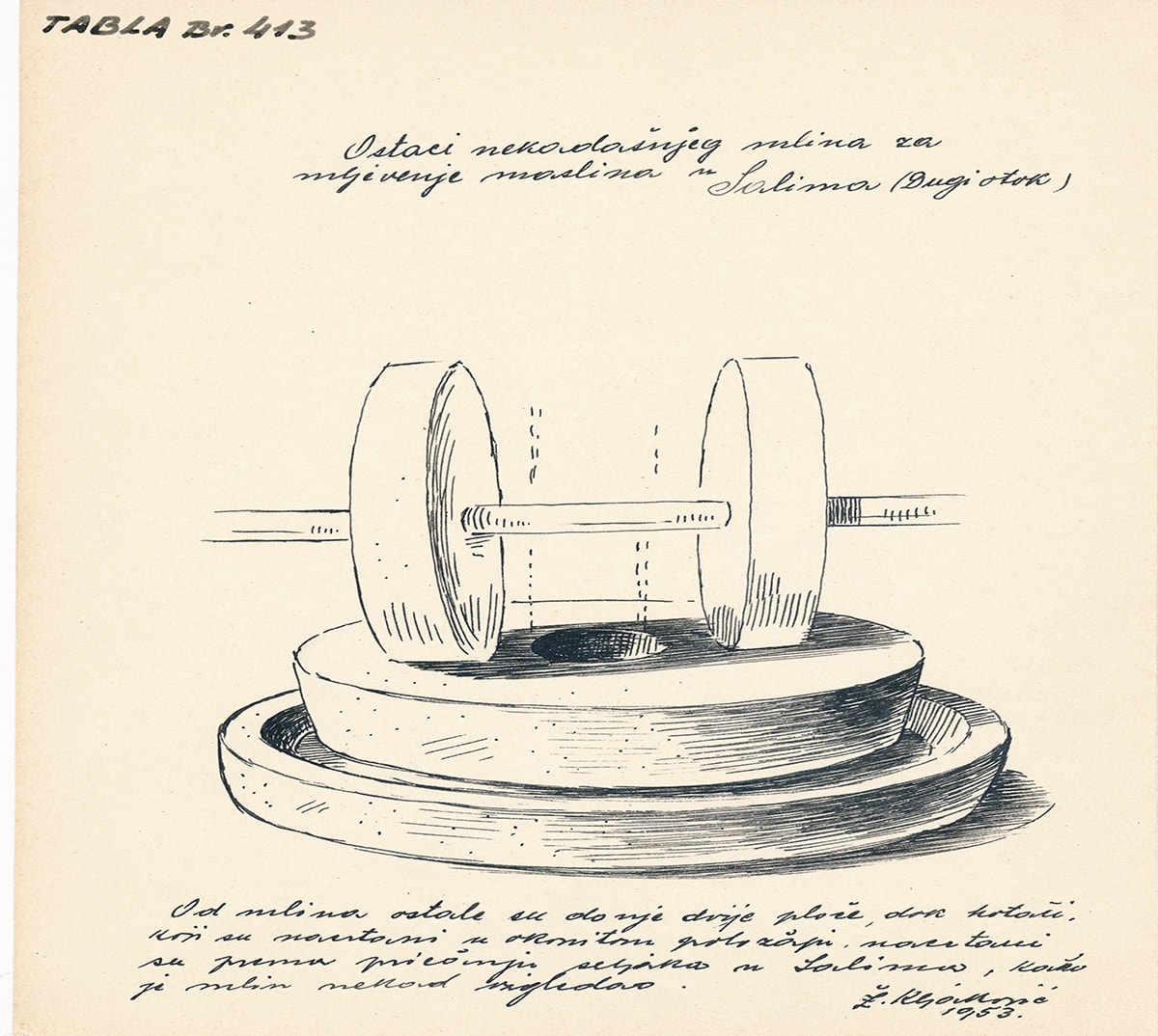

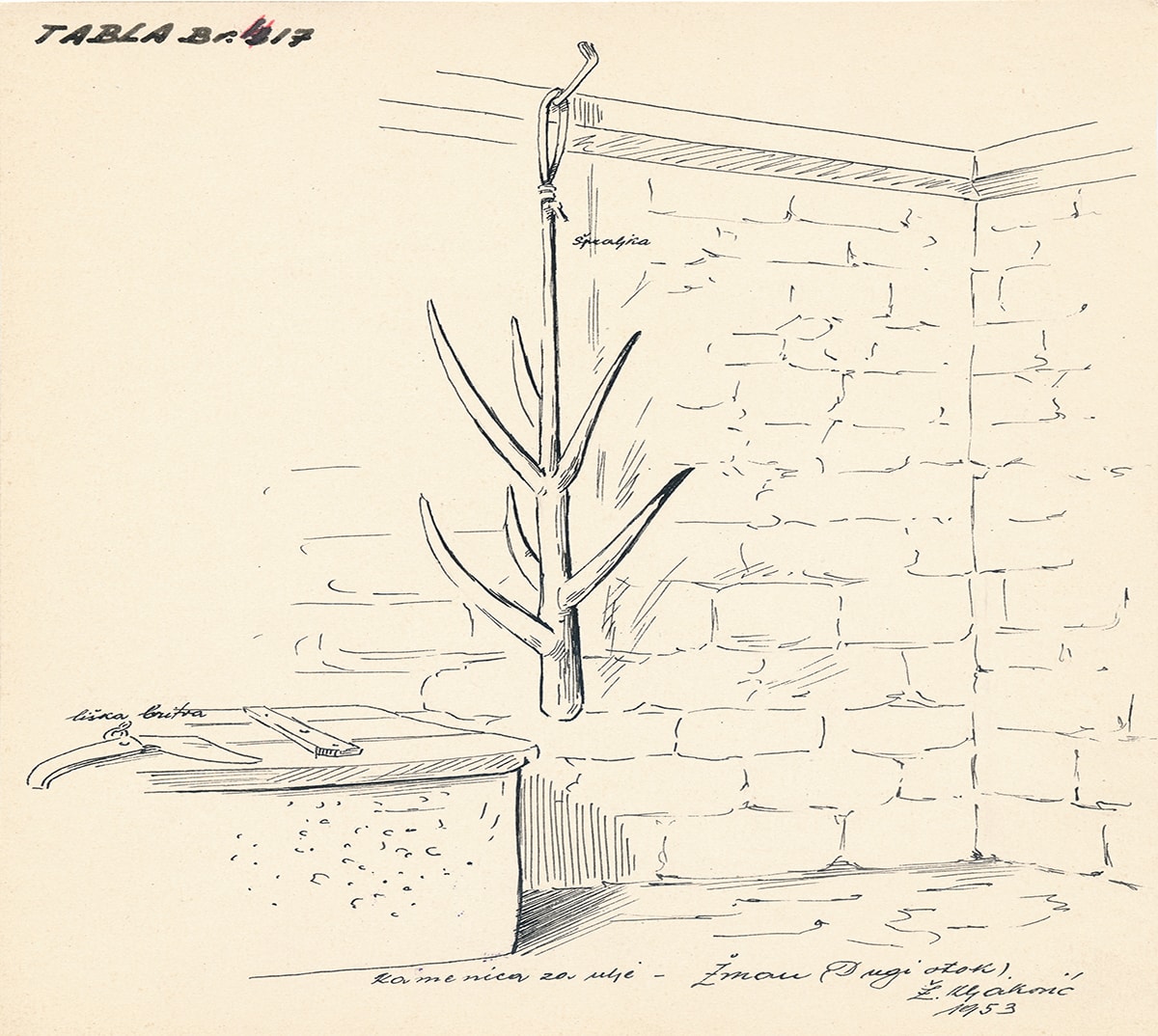

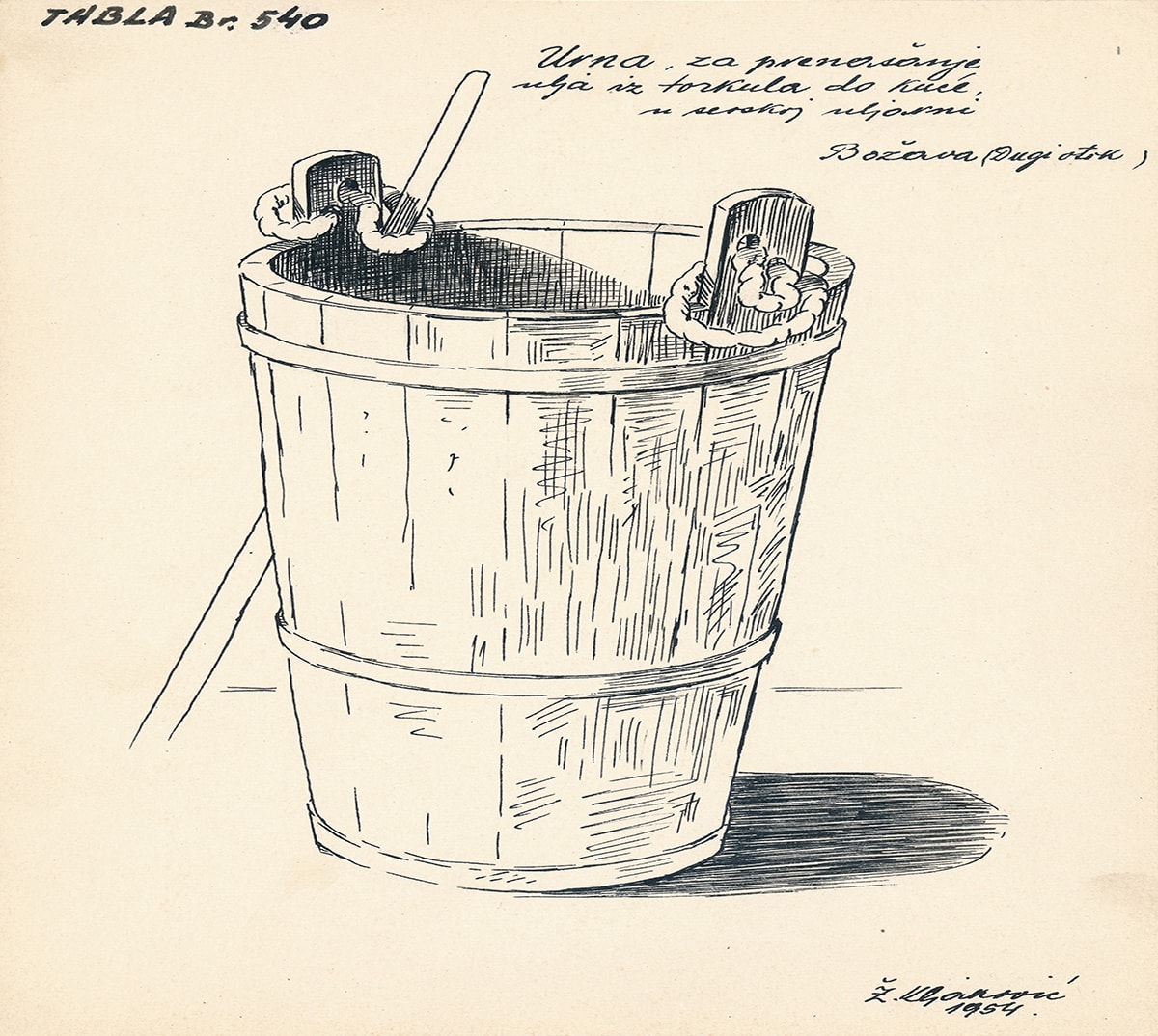

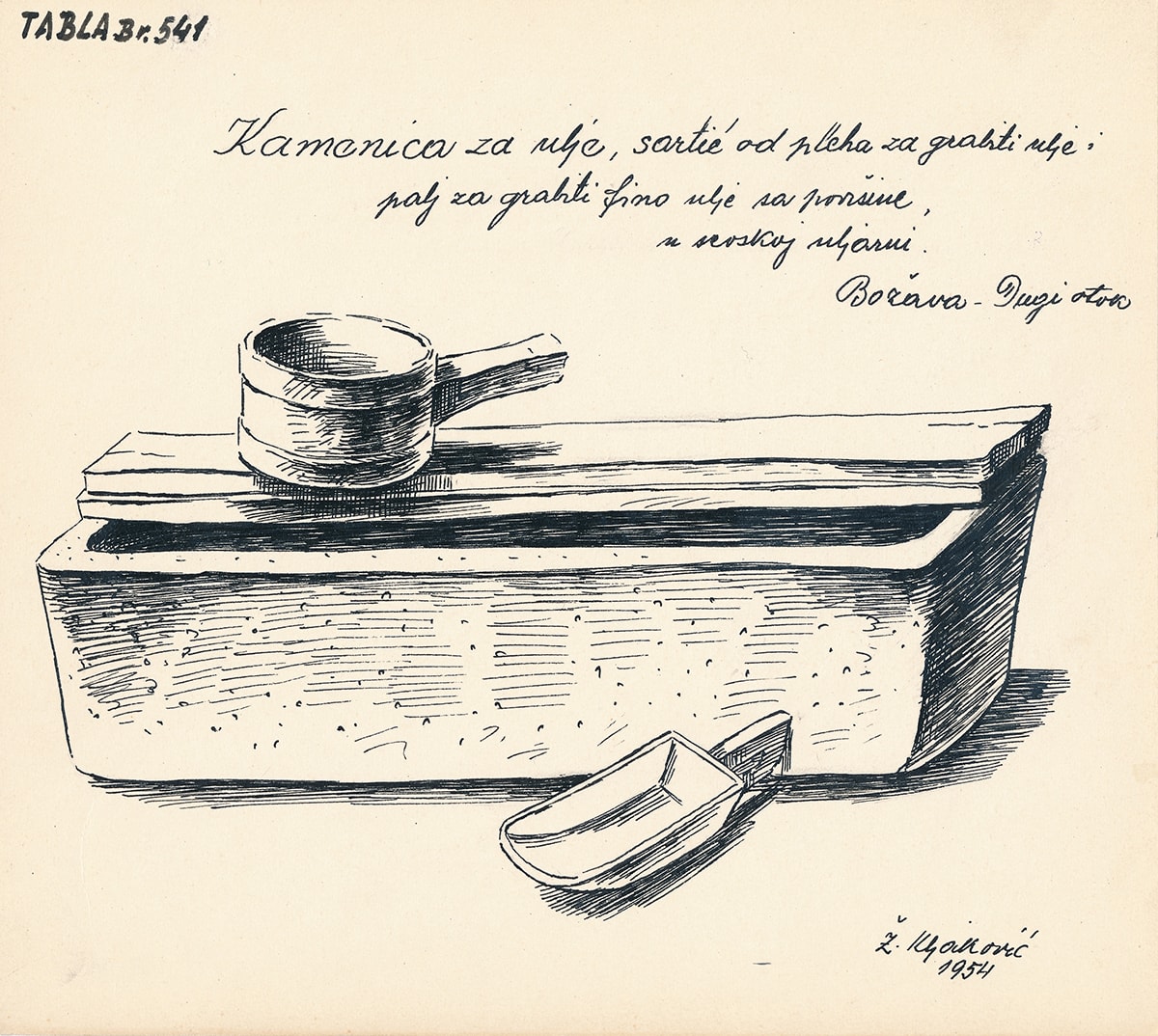

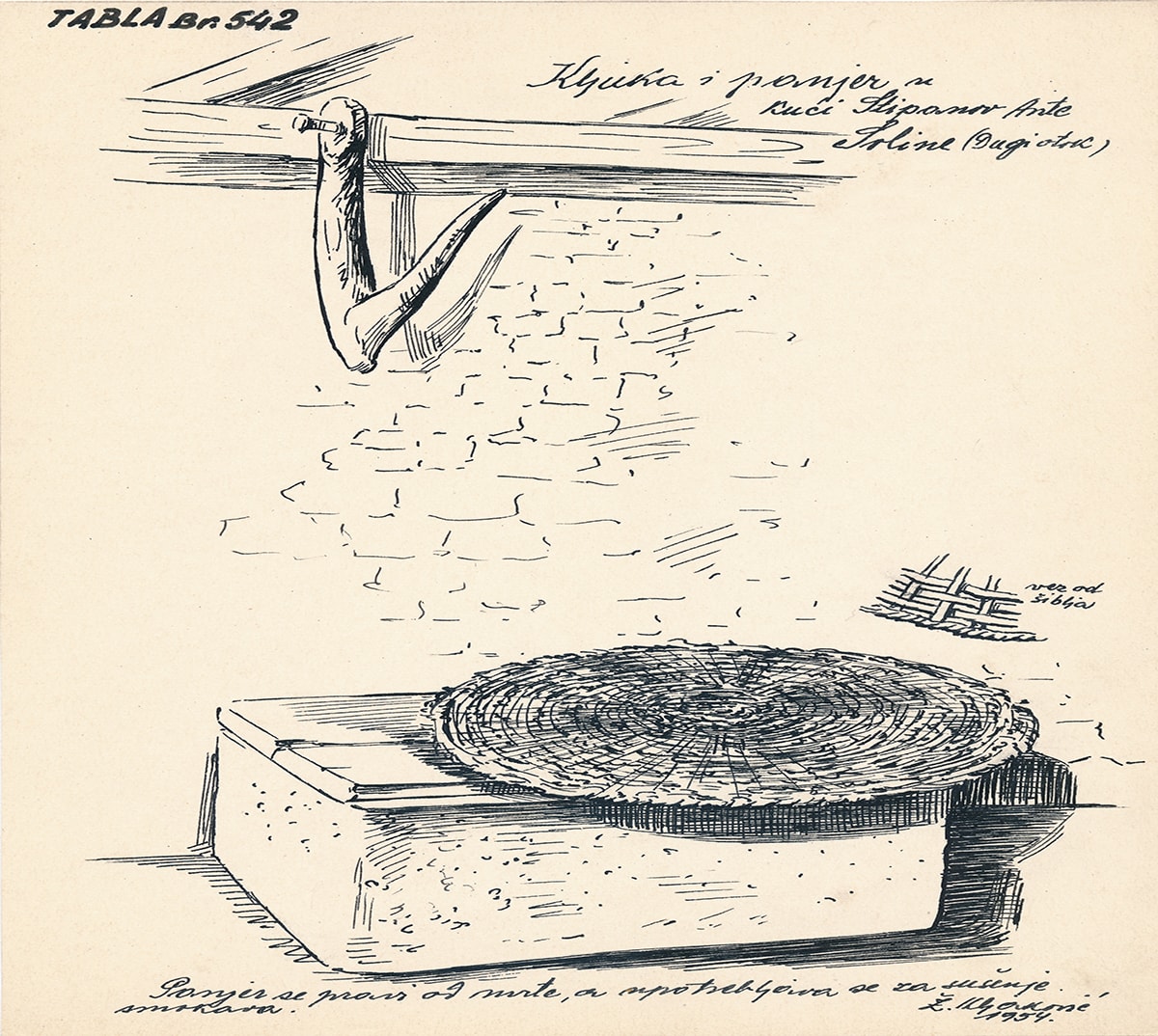

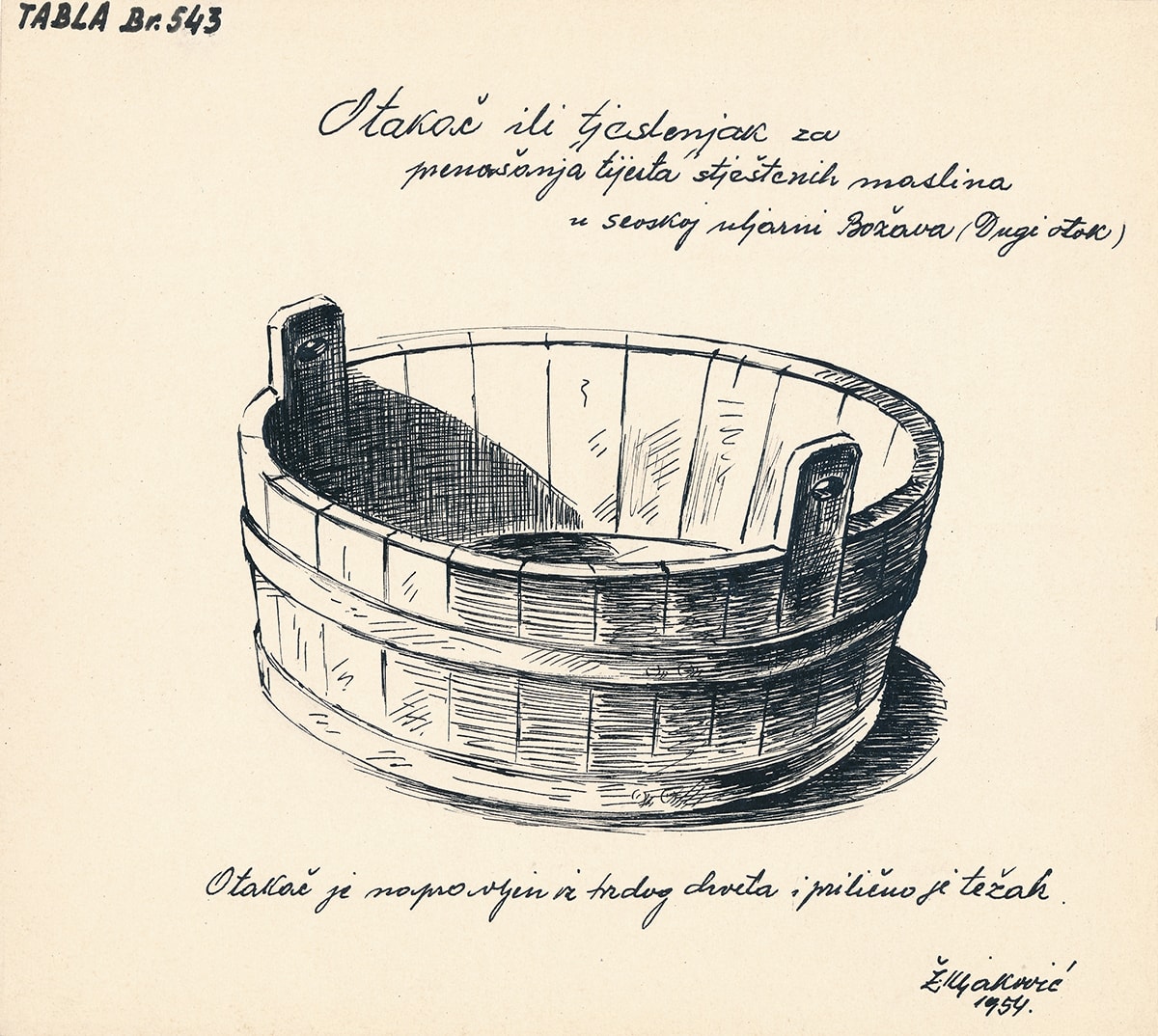

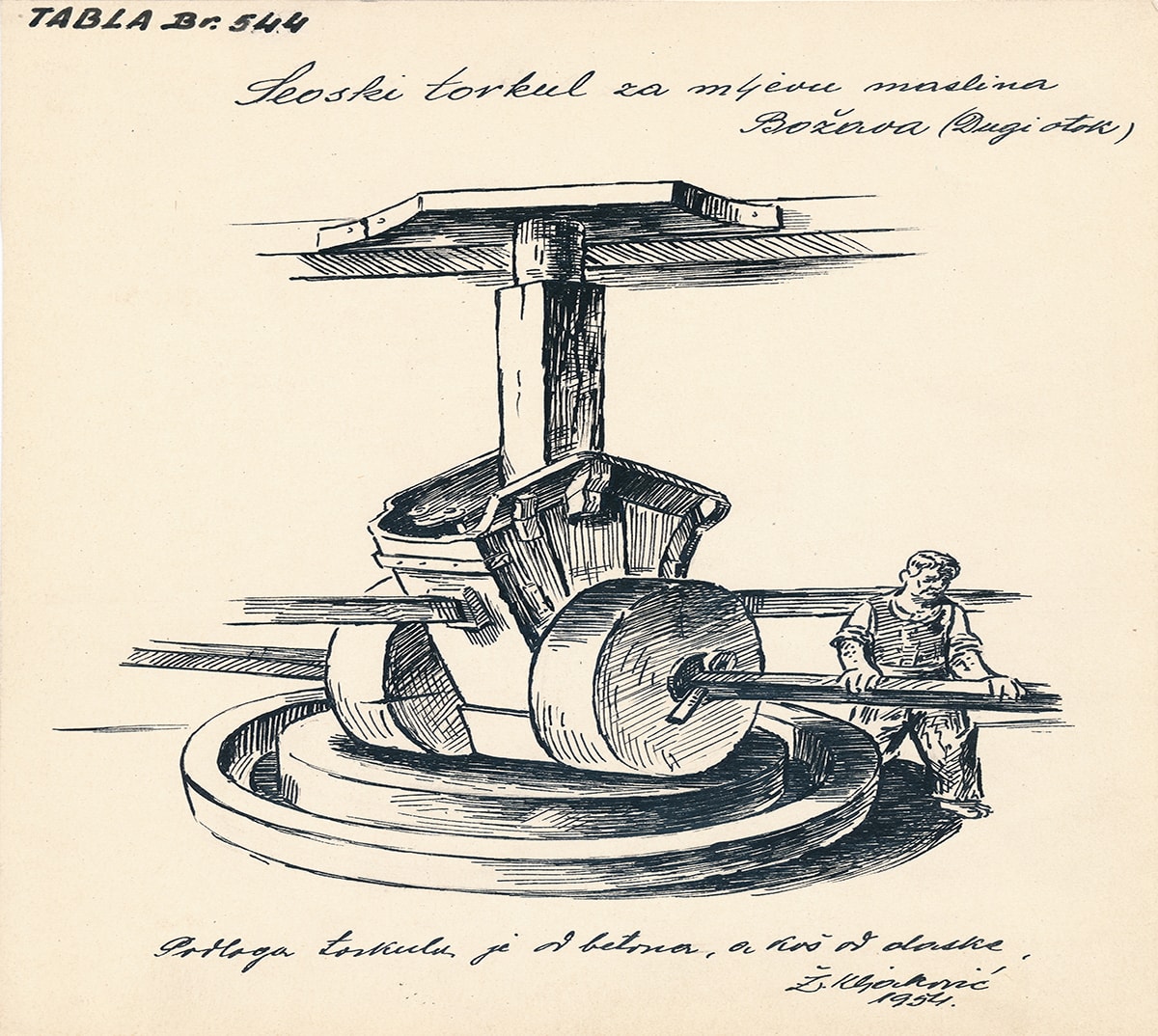

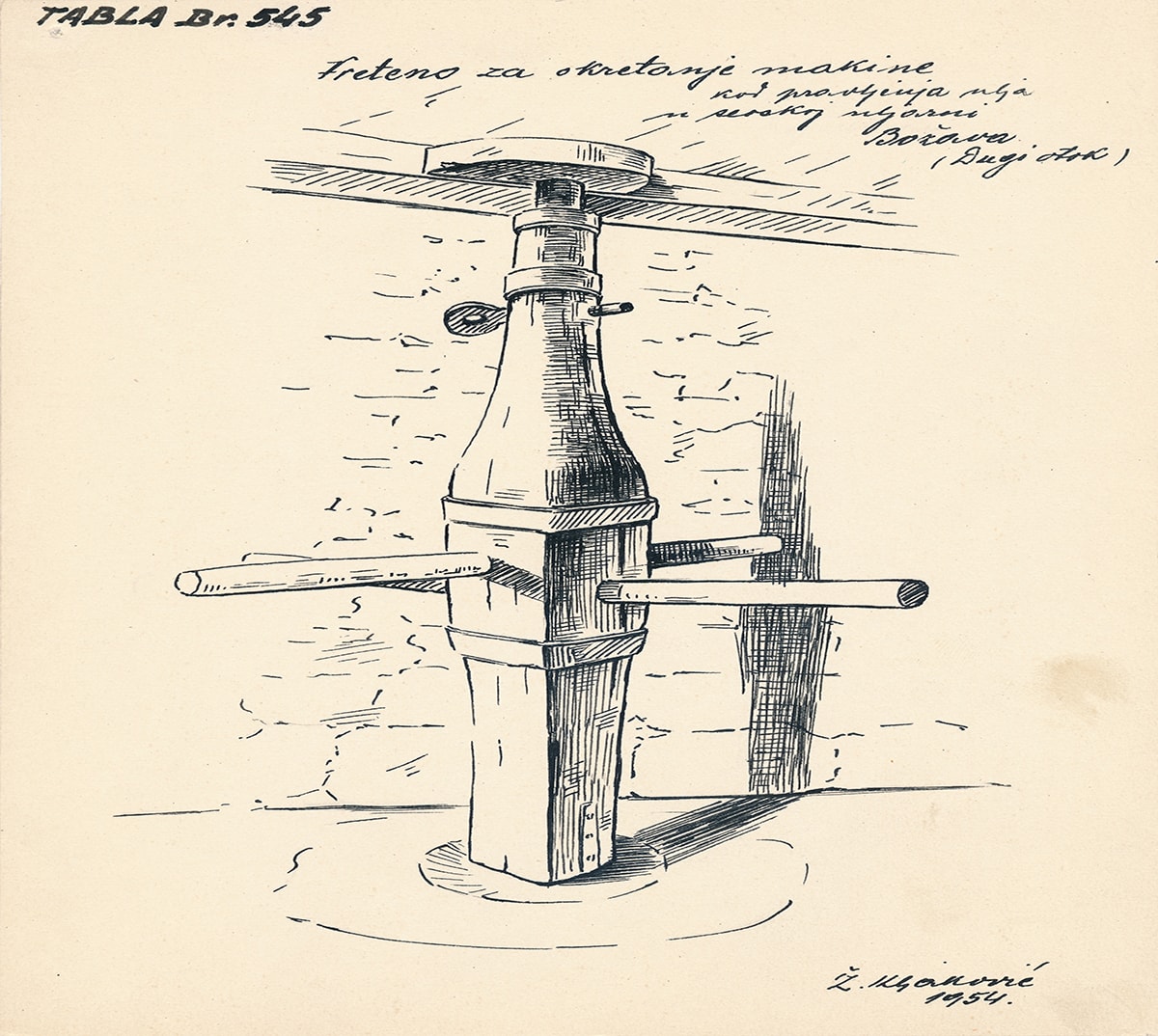

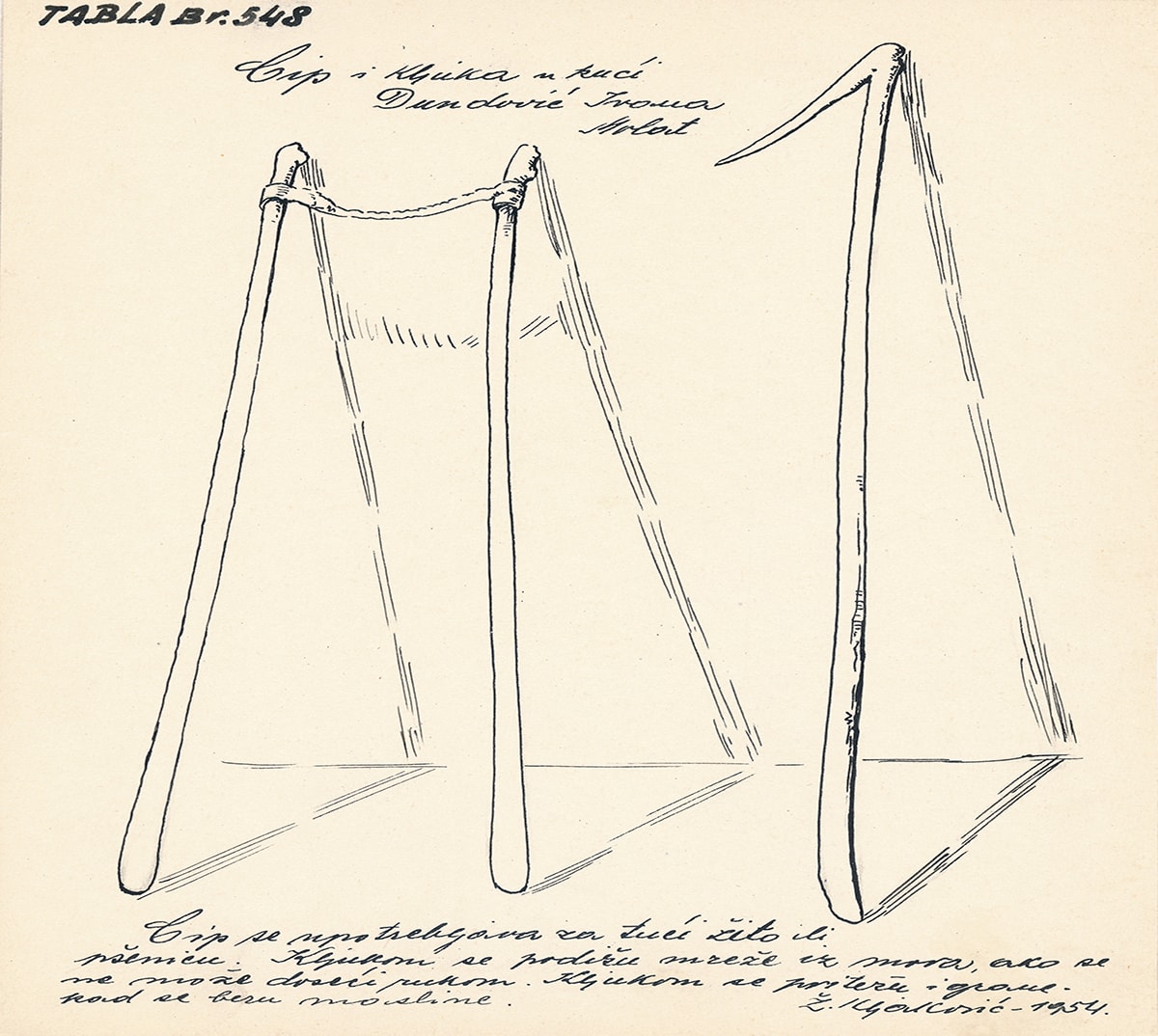

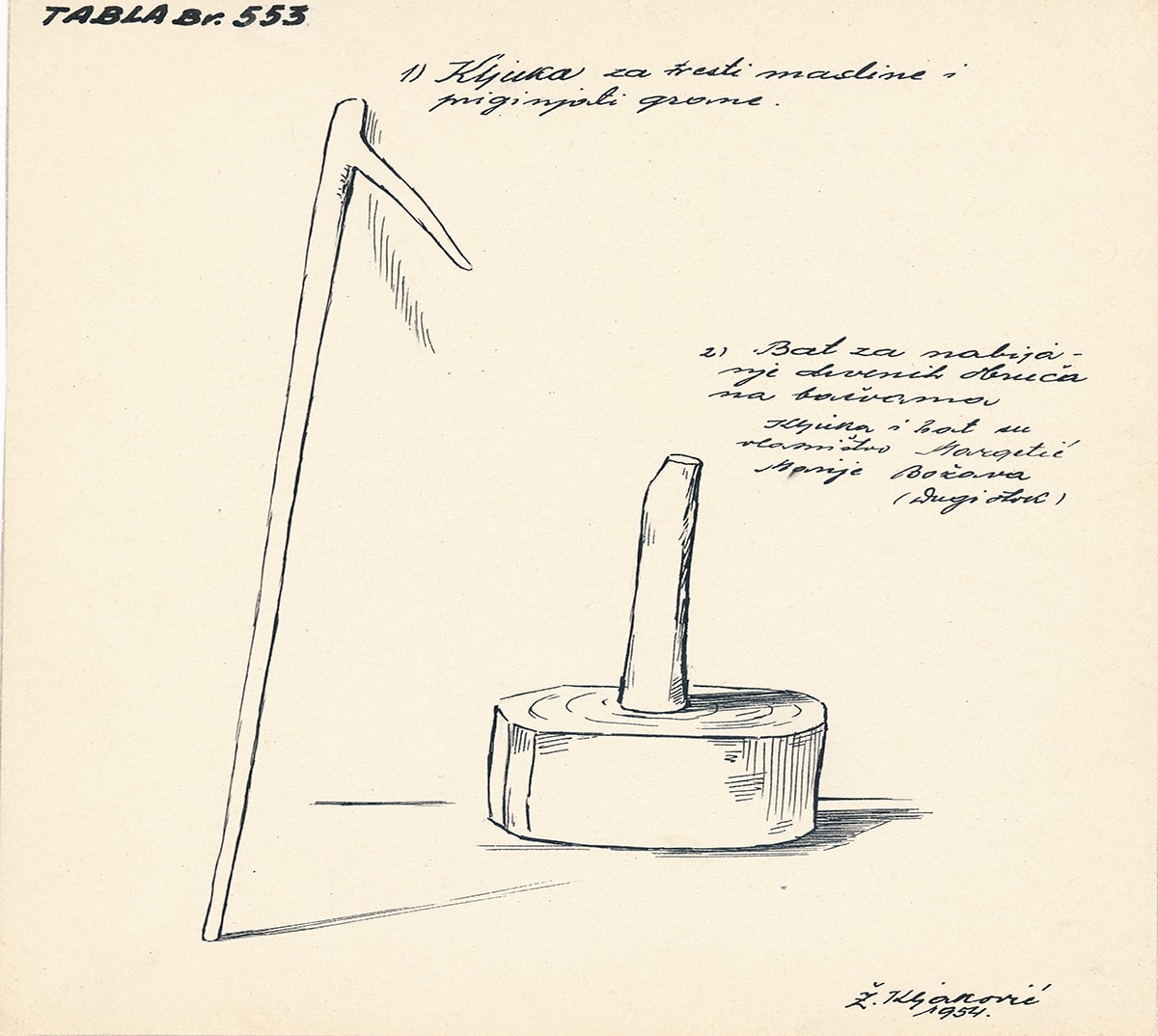

The people of Sali have since ancient times been engaged in olive growing. Due to its exceptional value, Saljsko Polje was proclaimed a botanical reserve in 1969. The old groves are located in the following fields: Dugo Polje, Stivanje and Arnjevo Polje, Jaz, Kršovo and Saljsko Polje. Their owners were landed gentry, and the people of Sali were serfs and gave them a certain part of their income. In the late 19th and early 20th century the people of Sali bought off the olive groves and started to work for their own benefit. The so-called fencesof olive groves are adorned by drywalls that separate the plots and protect the olive groves from animals and soil drifts during heavy rains. Picking olives requires patience. Cleaning olives, hoeing and removing weeds and grass was work performed mainly by women. Clean and tidy ground under the olive trees was a matter of prestige among the farmers. The picking would begin late in the winter, and it used to last until spring. The oldest way to get oil from the olives was to mash the fruits and pour hot sea water over them, and then collect oil from the surface. It was demanding and time consuming work. Olives were picked when they were ripe, unlike today when the picking begins while they are still green. Olives were picked by hand or by hitting the tree with a savin juniper stick called kljuka. Picked olives were put into bags and carried by donkeys to the house or to the bays in Telašćica, and then by boat to Sali. Until they were taken to oil factories, they were kept in barrels with water, more often sea water. Because of the need of processing olives on the island, there was a large number of oil factories, 9 in Sali. The oil factories operated on the principle of a stone mill, and it took 12 people to turn the mill. An interesting fact is that the mill was turned mainly by women. Only one large rock was used for milling (mashing olives) with a diameter of 120 cm and a thickness of 40 cm and a hole in the middle where a stronger beam of about 6 m in length. The stone revolved set onto an even greater round stone, and it was called škaljenica. Thother stone was in the ground, hidden under the room. It was indented as a plate, and in its middle it had a slot for bearing a wooden axle. The axle went all the way to the ceiling where it was drawn into the ceiling joist. Next to the wooden axle stood a wooden basket where olives were put, and by turning of the axle they fell onto the bottom stone. One of the workers needed to monitor the process and push olives under the stone with his feet. He had the role of the so-called stomper (gazač). Ground olives were called dough (tijesto). The dough was collected into the centre of the indentation of the stone which was turned by 8-12 women. The women were mostly young girls. The mashing would last 5-6 hours, mostly at night. The dough was then transfered into a wooden barrel, the so-called maštel, or lesa. In the floor, next to it, stood a wooden vessel where oil, the so-called noćnjak poured. The fresh oil was deemed as medicinal since ancient times because of its purity. As much dough as possible needed to be obtained during the night, so that it would be ready for the next day and the next phase, namely the pushing of the dough through a press, the so-called torkul. The press worked on the principle of a screw that was used to put pressure on the dough and squeeze all of its fluid out, including oil. The dough was taken from the barrel, put into round bags made of rope with a diameter of 1 m, which were put on top of each other to a height of up to 10 bags, each with a capacity of up to 30 kg. The press was lowered onto the stack of bags, squeezing out oil. A day’s work was done by 3-4 workers in a bent-over position because they were pushing the bar with their shoulders. Beside the pressing process, hot sea water was poured onto the press to melt the oil. It was possible to process up to 1200 kg of olives daily by working for 12 hours. The remaining dough, the so-called torkulada, was used as heating fuel, because the sea water necessary for melting the oil was heated on a special built-in boiler. All of the oil factories on the island worked using the same method. Today, with advanced technology, the factories use modern systems but the stone vessels for storing oil can still be found in inns and taverns, and olive oil is a mandatory part of every household.

Source of drawing:

˝Drawings of folk architecture, folk costumes and artifacts from Dugi Otok”, collection Ž. Kljaković, Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research, Zagreb (signature: IEF C 22)”

˝Drawings of folk architecture, folk costumes and artifacts from Sali, Zaglav and Žman”, collection Ž. Kljaković, Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research, Zagreb (signature: IEF C 18 )”